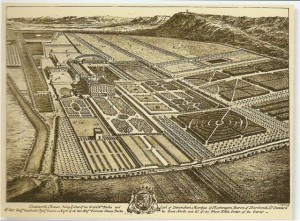

[caption id="attachment_1372" align="alignleft" width="300" caption="Chatsworth gardens as laid out in 1699"]

[/caption]

The first gardens that archeology uncovers are those made by the Egyptians. Walled cool courtyards carved out of the arid desert and based round water, the formal planting of date palms, papyrus and figs in rows. Since the making of the earliest gardens, there has been a certain tension between the garden as a retreat: a symbolic holy place associated with the Madonna and Garden of Eden or foretaste of paradise for the Muslim.

The greatest extant example of this are the gardens of the General Life and Alhambra which amaze and dazzle in Grenada. The layout of these gardens: geometric patterns, enclosure, rills and fountains has been borrowed over and over again by architects and designers.

The same idea of earthly paradise is present in the mughal gardens in India. Water is a very precious element and the gardens round the Dahl lake Kashmir may have cracked and empty basins, but the stonework and typical pattern of pavements and colonnades is still there.

The Romans - when it was their turn, revealed the other side of the tension: the extrovert. Gardens turned outside to enfold the landscape. Pliny the Younger had two villas- one in Tuscany and the other at the seaside. Both embraced the wide views lying beyond, annexed them in a sense. At the same time, the theories of the layout of landscape were evolving. In 30BC Vitruvius’s wrote “de Architectura” on the relationship between theatrical and garden design.

The Romans had a great love of pruning and training trees into fanciful shapes. There were t

opiarii, a specialist gardener class who hailed from Greece and were dab hands with single handed shear and sharp knives.

Buxus sempervirens was the chosen shrub and carved into hunting scenes, ships in full sail. Topiary and restrictive forms of pruning have been in and out of fashion ever since.

The Renaissance architects studied the ruins and patterns of layout. Classical proportions were reinterpreted for outdoor living. Annexed from the Arabs, the science of mathematics meant that perspective was in and with it the manipulation of space. The high Italian gardens of the time were laid out to be viewed from above. Symmetry, balance and harmony were the rules with the garden flowing out into wilder areas with grottoes and walks through bosky groves.

As Italy waned economically, France soared and the reign of Louis XIV was about absolute monarchy, absolute control and nature subordinated to man. Versailles spilled out, conquering-army style, to occupy the entire landscape. Trees marched in serried ranks, hedges were clipped, raised on stilts and lined up in allees. French rationalism in the hands of most famous designer of the day, Le Notre who worked at Versailles was to tyrannize nature. He used the theatrics of optical illusion and fake perspective. Versailles has a central axis leading to a vanishing point at the horizon where the garden disappears into infinity. Flowerbeds were curlicues filled with coloured stones. He came to England when Charles II returned from exile and set to work on the gardens at Hampton Court.

And yet a rumble of dissent began to be heard. The English had taken to travelling abroad, studying the landscape, the ruins, the works of art. The Landscape Movement began with William Kent (1685 - 1748). At Rousham in Oxfordshire, designed by him in 1738 (and still relatively there and unspoilt) he “leaped the fence and saw all nature was a garden” . The invention of the haha was a real help in all this.

The movement borrowed from the wild side of the Italian Renaissance gardens, took off; peppered with the politics, philosophy and agricultural advances of the day. It culminated in the English country landscape as we know it. Defined by grassy meadows, serpentine lakes, gently contoured hills and artfully arranged clumps of tree.

Formality was swept away and when Capability Brown had his run of patronage from the aristocracy, the fussy broderie minuteness of flower gardening near the house was banished to the Walled Garden, a suitable distance away. Our popular view of the English rolling landscape was Capability Brown’s vision and invention and has been our most famous export.

[/caption]

The first gardens that archeology uncovers are those made by the Egyptians. Walled cool courtyards carved out of the arid desert and based round water, the formal planting of date palms, papyrus and figs in rows. Since the making of the earliest gardens, there has been a certain tension between the garden as a retreat: a symbolic holy place associated with the Madonna and Garden of Eden or foretaste of paradise for the Muslim.

The greatest extant example of this are the gardens of the General Life and Alhambra which amaze and dazzle in Grenada. The layout of these gardens: geometric patterns, enclosure, rills and fountains has been borrowed over and over again by architects and designers.

The same idea of earthly paradise is present in the mughal gardens in India. Water is a very precious element and the gardens round the Dahl lake Kashmir may have cracked and empty basins, but the stonework and typical pattern of pavements and colonnades is still there.

The Romans - when it was their turn, revealed the other side of the tension: the extrovert. Gardens turned outside to enfold the landscape. Pliny the Younger had two villas- one in Tuscany and the other at the seaside. Both embraced the wide views lying beyond, annexed them in a sense. At the same time, the theories of the layout of landscape were evolving. In 30BC Vitruvius’s wrote “de Architectura” on the relationship between theatrical and garden design.

The Romans had a great love of pruning and training trees into fanciful shapes. There were topiarii, a specialist gardener class who hailed from Greece and were dab hands with single handed shear and sharp knives. Buxus sempervirens was the chosen shrub and carved into hunting scenes, ships in full sail. Topiary and restrictive forms of pruning have been in and out of fashion ever since.

The Renaissance architects studied the ruins and patterns of layout. Classical proportions were reinterpreted for outdoor living. Annexed from the Arabs, the science of mathematics meant that perspective was in and with it the manipulation of space. The high Italian gardens of the time were laid out to be viewed from above. Symmetry, balance and harmony were the rules with the garden flowing out into wilder areas with grottoes and walks through bosky groves.

As Italy waned economically, France soared and the reign of Louis XIV was about absolute monarchy, absolute control and nature subordinated to man. Versailles spilled out, conquering-army style, to occupy the entire landscape. Trees marched in serried ranks, hedges were clipped, raised on stilts and lined up in allees. French rationalism in the hands of most famous designer of the day, Le Notre who worked at Versailles was to tyrannize nature. He used the theatrics of optical illusion and fake perspective. Versailles has a central axis leading to a vanishing point at the horizon where the garden disappears into infinity. Flowerbeds were curlicues filled with coloured stones. He came to England when Charles II returned from exile and set to work on the gardens at Hampton Court.

And yet a rumble of dissent began to be heard. The English had taken to travelling abroad, studying the landscape, the ruins, the works of art. The Landscape Movement began with William Kent (1685 - 1748). At Rousham in Oxfordshire, designed by him in 1738 (and still relatively there and unspoilt) he “leaped the fence and saw all nature was a garden” . The invention of the haha was a real help in all this.

The movement borrowed from the wild side of the Italian Renaissance gardens, took off; peppered with the politics, philosophy and agricultural advances of the day. It culminated in the English country landscape as we know it. Defined by grassy meadows, serpentine lakes, gently contoured hills and artfully arranged clumps of tree.

Formality was swept away and when Capability Brown had his run of patronage from the aristocracy, the fussy broderie minuteness of flower gardening near the house was banished to the Walled Garden, a suitable distance away. Our popular view of the English rolling landscape was Capability Brown’s vision and invention and has been our most famous export.

[/caption]

The first gardens that archeology uncovers are those made by the Egyptians. Walled cool courtyards carved out of the arid desert and based round water, the formal planting of date palms, papyrus and figs in rows. Since the making of the earliest gardens, there has been a certain tension between the garden as a retreat: a symbolic holy place associated with the Madonna and Garden of Eden or foretaste of paradise for the Muslim.

The greatest extant example of this are the gardens of the General Life and Alhambra which amaze and dazzle in Grenada. The layout of these gardens: geometric patterns, enclosure, rills and fountains has been borrowed over and over again by architects and designers.

The same idea of earthly paradise is present in the mughal gardens in India. Water is a very precious element and the gardens round the Dahl lake Kashmir may have cracked and empty basins, but the stonework and typical pattern of pavements and colonnades is still there.

The Romans - when it was their turn, revealed the other side of the tension: the extrovert. Gardens turned outside to enfold the landscape. Pliny the Younger had two villas- one in Tuscany and the other at the seaside. Both embraced the wide views lying beyond, annexed them in a sense. At the same time, the theories of the layout of landscape were evolving. In 30BC Vitruvius’s wrote “de Architectura” on the relationship between theatrical and garden design.

The Romans had a great love of pruning and training trees into fanciful shapes. There were topiarii, a specialist gardener class who hailed from Greece and were dab hands with single handed shear and sharp knives. Buxus sempervirens was the chosen shrub and carved into hunting scenes, ships in full sail. Topiary and restrictive forms of pruning have been in and out of fashion ever since.

The Renaissance architects studied the ruins and patterns of layout. Classical proportions were reinterpreted for outdoor living. Annexed from the Arabs, the science of mathematics meant that perspective was in and with it the manipulation of space. The high Italian gardens of the time were laid out to be viewed from above. Symmetry, balance and harmony were the rules with the garden flowing out into wilder areas with grottoes and walks through bosky groves.

As Italy waned economically, France soared and the reign of Louis XIV was about absolute monarchy, absolute control and nature subordinated to man. Versailles spilled out, conquering-army style, to occupy the entire landscape. Trees marched in serried ranks, hedges were clipped, raised on stilts and lined up in allees. French rationalism in the hands of most famous designer of the day, Le Notre who worked at Versailles was to tyrannize nature. He used the theatrics of optical illusion and fake perspective. Versailles has a central axis leading to a vanishing point at the horizon where the garden disappears into infinity. Flowerbeds were curlicues filled with coloured stones. He came to England when Charles II returned from exile and set to work on the gardens at Hampton Court.

And yet a rumble of dissent began to be heard. The English had taken to travelling abroad, studying the landscape, the ruins, the works of art. The Landscape Movement began with William Kent (1685 - 1748). At Rousham in Oxfordshire, designed by him in 1738 (and still relatively there and unspoilt) he “leaped the fence and saw all nature was a garden” . The invention of the haha was a real help in all this.

The movement borrowed from the wild side of the Italian Renaissance gardens, took off; peppered with the politics, philosophy and agricultural advances of the day. It culminated in the English country landscape as we know it. Defined by grassy meadows, serpentine lakes, gently contoured hills and artfully arranged clumps of tree.

Formality was swept away and when Capability Brown had his run of patronage from the aristocracy, the fussy broderie minuteness of flower gardening near the house was banished to the Walled Garden, a suitable distance away. Our popular view of the English rolling landscape was Capability Brown’s vision and invention and has been our most famous export.